Information

Journal Policies

ARC Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics

Volume-1 Issue-3, 2016

2.KEYWORDS

3.INTRODUCTION

4.MATERIALS AND METHODS

5.RESULTS

6.DISCUSSION

7.REFERENCES

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate PPI as a strategy to make ART affordable.

Design: Prospective descriptive study.

Setting: Tygerberg Academic Hospital, Reproductive Medicine Unit.

Population: All women ages 20-45 years attending the fertility clinic for ART (IVF/ICSI) treatment for female and male infertility problems

Methods: Treatment involved CC 100mg from cycle day 3 to 7 or day 3 to 10 in combination with alternate day administration of hMG 150-225IU from cycle day 4, 6 and 8. hCG was administered when the leading follicle of ≥18mm was present and the retrieval followed 34-36hrs later. Cycle monitoring included only the ultrasound and urinary LH testing.

Main outcome measures: LBR, CPR and also the direct costs of treatment to individual couple per cycle of ART.

Results: Three hundred and seventy five (375) cycles of ART were performed. The LBR per ET and per cycle started were 17.7% and 10.6% respectively, while the CPR per ET and per started cycle were 24% and 14% respectively. A cycle cancellation rate of 8% was observed. A multiple pregnancy rate of 5.6% was recorded and there were no cases of OHSS. Direct costs of treatment per cycle were R7291 (563USD) (cycle costs R6000 – R8000). A cumulative pregnancy rate of 32% following three cycles of ART was also observed.

Conclusion: The study shows that PPI can be a possible and viable strategy to make ART accessible with reasonable pregnancy rates at low cost.

Tweetable abstract: PPI can be a possible and viable strategy to make ART accessible with reasonable pregnancy rates at low cost.

AUTHOR DETAILS

Nathan A. Keller

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Albany Medical Center

16 New Scotland Avenue, Second Floor, MC-74 Albany, New York,

Nathan A. Keller – Medical Doctor

No grants or financial supporters to report

[email protected]

INTRODUCTION

Infertility is undeniably a public and global health issue [1]. With over 5 million children beingborn following ART worldwide, this technique is still not widely available or used in eitherdeveloping and developed countries because of its high costs [2].The availability of funding or health insurance facilities for ART differs worldwide with optimal coverage in Belgium to absolutely no cover in the United States of America (USA) [3-5]. Cost is the major limiting factor and number one deterrent for infertile couples to seek ART treatment [6, 7]. The cost drivers of IVF cycle in a relatively large private clinic are mainly medication (28%), clinicians' fees and consultation (29%), and laboratory fees (35%) [8]. The first report on ART data monitoring in South Africa and sub-Saharan Africa (developing countries) shows that the ART needs of many couples are still unmet, with only 6% coverage [9]. This issue receives very little attention because most governments and authorities in the developing countries are faced with major health challenges such as high maternal morbidity and mortality, and infectious diseases including TB, HIV and malaria [10].

However the desire to have children especially in the developing countries presents much stronger negative psychosocial consequences from psychological distress, domestic violence, stigmatization and polygamy [11-13]. Studies have shown that to have a healthy child, couples may accept a 20% risk of death and give up 29% of their income [14].There are more than 80 million couples affected by infertility worldwideand the majority of this population resides in the developing countries where funding for ART does not exist [15]. This protracted and painful undesired situation of childlessness for millions of couples in the developing countries hasbeen well expressed by Murage et al. in a crosssectional survey, showing that 26.1% of gynaecologic consultations in Kenya were related to subfertility and 50.3% were due to tubal factors, while 14.8% were due to male factors [16]. It has been shown that by reducing the cost of treatment and improving access to treatment is associated with improved patient safety and reduction inundesirable complications of high order multiple pregnancies [3, 17]. This situation is to be avoided at all possible costs in poorly resourced countries.

The current paper seeks to evaluate and demonstrate PPI as a possible strategy to make ART accessible in the very limited resources settings by describing a series of patients managed through the model.

A Description of the First 375 Cyclesmanaged with ART through PPI Model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design: Pragmatic, prospective descriptive study

Setting: The ART treatment was provided by the Reproductive Medicine Unit at Tygerberg Academic Hospital (public)

Data Collection The study included all women who underwent ART in the form of IVF and ICSI in our unit from 2011 to 2014. It was couples who required ART irrespective of the diagnosis, age (limit ≤42 yrs of age), BMI (kg/m2) [limit 7lt;36]. There was no specific exclusion criterion for couples in their first cycle of ART. The patients were counselled on the treatment protocol, the cost of treatment and the success rates that are lower than those of conventional ART programmes.

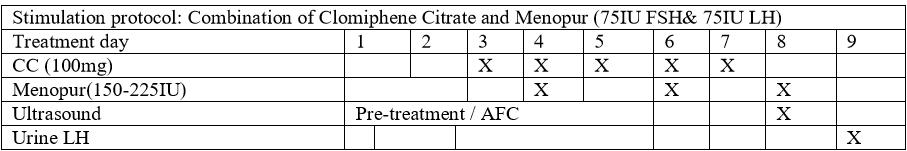

Mild Ovarian Stimulation Protocol (Figure 1)

The patients were stimulated with CC (Fertomid, Cipla MEDPRO RSA) 100mg for 5 days from menstrual cycle 3 to 7 and hMG(Menopur, FERRING, SA) 150-225 lU (2-3 ampoules) that was added on cycle day 4, 6, 8 and/or 10. Follicular monitoring began on cycle day 8 and was performed every alternate day until the day of hCG administration. Urine LH tests were performed from cycle day 9 and every alternate day and sometimes daily until the day of hCG administration. No endocrine biochemical tests were prepared as part of monitoring. In cases where spontaneous ovulation is highly suspected based on follicular size (>22mm) and weak positive urinary LH before hCG administration, NSAIDs Indomethacin (Arthrexin, Adcock Ingram SA) 25mg three times a day will be offered until the day of oocyte retrieval [18].hCG (Ovitrelle, Merck SA) 250mcg/0.5ml was administrated where there wasa leading follicle of >18mm. Oocyte retrieval was performed 34-36hours after hCG administration by ultrasound guided puncture of follicles, and IVF or ICSI was performed.

Laboratory – Oocyte Retrieval, Insemination and Embryo Transfer

Oocyte retrieval is done under conscious sedation without the need for anaesthesia, an anaesthetist or a theatre set-up. Patients receive Pethidine 100 mg intramuscularly 15-30 minutes before procedure and a 20ml local block with 1% Lignocaine without Adrenaline. Sperm will be prepared on the day of oocyte retrieval using 3-layer density gradient centrifugation (90%–70%–40%) (PureSperm, Nidacon) followed by two washing steps in Earle's Balanced Salt Solution + 5% Human Serum Albumin (HSA). Samples will be re-suspended in Global® (G-IVF, Life Global, USA) + 5% HSA and incubated at 36.5°C until fertilization. Oocyte-cumulus-complexes were placed in a 5ml tube with 1ml Global® for fertilization + 5% HSA (pre-equilibrated) and a volume equivalent to 50 000 to 100 000 motile sperm added. Fertilization and embryo culture will occur in a tissue culture incubator in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air, with confirmation of fertilization made 16-20 hours later. All embryos were assessed and scored morphologically before transfer [19]. ET was performed on day 2 or 3 under ultrasound guidance with a SageET catheter. Occasionally ET was performed on day 5. Cryopreservation facilities are available when necessary.

Luteal support with vaginal progesterone (Utrogestan, Medi Challenge SA) 400mg daily was started on the day of ET and continued until the day of the quantitative pregnancy test. The cycle was cancelled if there was no follicular growth, no oocytes retrieved during aspiration, no fertilization and poor embryo growth. Implantation was confirmed by measuring serum ß-hCG levels on day 10 and 12 following ET (> 25lU on day 10 confirmed pregnancy).

CPR is defined as the ultrasound presence of foetal cardiac activity at 7 weeks of gestation and OPR as the presence of foetal cardiac activity at >12 weeks of gestation. LBR is defined as the birth of a singleton, live baby at term.

The primary outcome measure was to show whether public-private interaction can make ART affordable, looking at the cost of treatment cycle and the outcomes, in terms of live birth rate.

Secondary outcomes include the number of oocytes retrieved, fertilization rates, clinical pregnancy rates, miscarriage rates and ectopic rates.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as percentages (n) and means ± SD or range.

The Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were used for prediction of pregnancy probability given the number of treatment cycles. The student t-test was used to compare the means anda p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

All analyses were performed with Stata 13 software.

RESULTS

A total of 375 cycles were performed with this low cost model between 2011 and 2014. The average age of women was 34.9 ± 4.7 (oldest was 44 yrs) and the most commonindications for treatment were tubal disorder (45.6%) and teratozoospermia (28.6%) (Table1). A total of 346 cycles (92%) reached oocyte retrieval stage. The cycle cancellation rate in this study was 8%. At the time of aspiration no oocytes were obtained in 10.7% (37/346) of the cases despite the presence of the expected number of follicles, and in 16.7% of the cases there was no fertilization. In addition, 7.5% of the cases did not reach embryo transfer stage as a result of poor quality embryos (Table 2).

IVF and ICSI were performed in 202 (53.8%) and 167 (44.5%) cycles respectively.The mean number of oocytes retrieved was 4.3 ± 4.0 (0-20). There were significantly more failures with IVF, 38/58(65.5%) than ICSI, 20/58(34.5%) p=0.0008. The mean number of embryos transferred was 2.99 ± 0.93 (range 1-4), with 77% (389/503) of good quality embryos available for transfer.A clinical pregnancy rate of 14.1% (53/375) per started cycle and 23.5% (53/225) per ET was achieved. Twelve clinical pregnancies ended in miscarriages 22.6% (12/53) and 1 ended as an ectopic pregnancy (tubal) (1.9%). Therefore a total of 40 babies were born, giving a LBR per stated cycle of 40/375 (10.6%) and LBR per ET of 40/225 (17.7%).

A multiple pregnancy rate of 5.6% (3/53) was recorded and it was only twins, with no triplets observed. No cases of OHSS were recorded (Table 3).

The probability of achieving a pregnancy following one, two and three cycles of IVF were 14.1%, 19.8% and 31.7% respectively (Table 4, Figure 2).There was no improvement in pregnancy chance between cycles 4 to 6 of treatment.

The overall cost of IVF/ICSI cycle is R7291.00 (563USD) which is direct cost to patient, and in the private clinics the cycle cost varies betweenR35000 and R50000 (3 861 USD)(Table 5). Further cost comparison shows that infrastructure (rental fees), personnel salaries, medication and laboratory costs are the greatestcost drivers in IVF/ICSI treatments (Table 5).

UPFS = Uniform Patient Fees Schedule, * Not always new, ** Direct costs to patients in 2012, there could be new figures, *** Price tag of IVF cycle which vary from clinic to clinic, α Estimated costs to company (clinic) based on one personnel in human resource categories (multiply by added number where applicable in big clinics). This cost is excluding medication and blood test fees.

DISCUSSION

There is an increasing demand, utilization and applications of ART worldwide owing to both the increasing effectiveness of treatment and the increasing rates of subfertility as couples delay childbirth [6]. The rising trend of utilization has been observed in the developed countries, particularly where there is public funding for ART [20]. However in the developing countries access to ART remainsnothing but a dream to be realised[21], largely because of the high cost and unaffordability of treatment [6,7,16, 22].

In this current study we present a PPI model in a limited resource setting.According to the draft health charter, PPI is defined as one or more persons or entities involved in health care within the public sector interacting with one or more persons or entities involved in health care within the private sector or the non-governmental organization sector with the intention to achieve mutual benefit. This includes public-private partnership (PPP) and PPI [23].The relationship may be a once-off involvement or be on an ongoing basis.

An optimally functioning laboratory is a prerequisite to ensure good results in ART and the public hospital (Tygerberg Hospital) provided the infrastructure in which the clinic and the laboratory provided the platform for consultation, monitoring and performance of ART treatment. Furthermore, the FMHS of Stellenbosch University contributed towards the laboratory infrastructure development through the purchase of the incubator, and the private clinic (Drs Aevitas) also donated the old ICSI machine and incubator tothe laboratory. This are meaningful once off contributions and similar interactions have been observed in other countries like Brazil [24].

Personnel competence and commitment is vital tosuccessful implementation of effective ART services [25]. In this current model the reproductive medicine specialists and embryologists are the employees of the University and the Government respectively. Therefore their remuneration isfully subsidised by their respective employers at no direct cost to patients (Table 5). In the private setting the clinician's fees and consultation contribute 29% (R14500 / 1120 USD) towards IVF cost, and this is a direct cost to the individual couple. There are no IVF sisters, nurses or co-ordinators in this currently presented model, further reducing the cost of treatment.

In this study, we used a combination of CC and hMG for ovarian stimulation at a cost of R3500– R4000 (270-308 USD) (Figure 1) as opposed to conventional ovarian stimulation at a cost of R14000 (1081 USD) [8].Similar protocols such as ours have been used with reasonable success [26]. The cycles in this current model were monitored with an ultrasound and urinary LH testonly. Due to lack of clear evidence to suggest any significant benefit in improving IVF outcome or predicting OHSS probability, the biochemical endocrine blood tests were not performed [27,28]. Palmeret al. have shown with a high degree of sensitivity that urine LH tests can predict ovulation in advance [29]. The cost of oocyte retrieval was also lowered quite significantly, by performing the procedure in the ART laboratory with adequate monitoringand resuscitationfacilities nearby. The patients were offered 100mg of pethidine injection15-30 minutes before procedure and were also injected locally with 1% Lignocaine at the puncture site. This approach eliminated the need for a theatre and anaesthetist (Table 5).

Laboratory costs account for 35% (R17 500 / 1351 USD) of the IVF cycle in private clinics [8]. In our model the couple pay for consumables such as media, plastics and slides on average R364 (28 USD) per cycle of IVF/ICSI. The patients will also pay an additional fee of R500 (38.60 USD) for ICSI pipettes if necessary. The total minimum cost of the IVF/ICSI cycle could amount to R122326 (9446 USD) in the public unit versus R187000 (14440 USD) in the private facility, and the couple's direct cost to treatment is approximately R7 291 (563 USD) versus R51 024 (3940 USD) for public and private facilities respectively (Table 5).These figures illustrate the significant contribution made by the government (hospital and/or university) through participation and commitment in the model. The mean number of oocytes retrieved per cycle was 4.3 ± 4.0, which is lower than the number of oocytes collected in conventional IVF. Sunkara et al. reported that approximately 15 eggs are required in conventional IVF cycles to improve the live birth rate [30]. Despite the low number of oocytes retrieved, the mean number of good quality embryos available for transfer on day 2/3 in this study was 2.09 ± 2.36 / 2.02 ± 2.01 respectively. Similar findings of a lower number of oocytes retrieved during mild ovarian stimulation cycle butwhich yieldeda higher number of good quality embryos and satisfactory pregnancy results were observed in a randomised controlled trial by Hohmann et al.[31]. The clinical pregnancy rate of 14.1% per started cycle and 23.5% per ET were achieved. These results are similar to those reported in the previous studies [22,32-34]. The live birth rates in this study were 10.6% per cycle and 17.7% per ET. Lower outcomes but similar to those observed by Aleyamma et alin an affordable IVF study [22].

This low cost model study shows that there were 237 first attempt cycles of ART and only 37 (9.8%) cycles were third time attempts. The financial limitation as a strong barrier towards treatment accessibility was the primary reason for the significant drop (Table 2). In this study the couple had a 14.1% chance of pregnancy after the first cycle of ART, 19.8% after the secondcycle and 31.7% after the thirdcycle (Figure 2). It means that for a couple to achieve results above 30% of pregnancy in a low cost model, they will need atleast three cycles of ART, and thiswill cost them approximately R22000 (1698 USD). This study demonstrates that even though the pregnancy outcomes are lower in the low cost model than in conventional IVF, the model does provide access and hope to those couples who might not have had a chance at all to try and possibly succeed with IVF

There were only three sets of twins (5.6%) observed throughout the study period and no cases of OHSS were reported. It is important to recognize that even in the low cost ART, a 26% rate of multiple pregnancies was reported and thisis high [22].In poorly resourced countries with overburdened services, the negative outcomes of treatment should be avoided at all costs.

Beyond providing simple access to treatment, ART has been shown to reduce the risk of HIV transmission in serodiscordant partners [35]. Therefore further proposes a strong argument to make ART affordable and accessible in order to protect the uninfected partner in a heterosexual relationship [36-38]. The availability of ART service in the public hospital, particularly a teaching hospital, also provided a platform to promote and improve teaching and training

In conclusion, PPIas illustrated in this study, appeared to make ARTaccessible and allowed couples the opportunity to undergo treatment, therefore presenting a viable strategy towards ART provision in limited resource settings. In our opinion, this model can be reproduced and be implemented successfully in developing countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to recognize and thank Mrs Brummer for her assistance with preparation of the manuscript. We also acknowledge the commitment and hard work of the laboratory staff at Tygerberg Reproductive Medicine Unit.

CONTRIBUTION TO AUTHORSHIP

TM was involved with conception, planning, carrying out, analysing and writing up. TK was involved with conception, planning and editing of the manuscript. MZ was involved with the analysing of data.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (FMHS) of Stellenbosch University in 2011 with reference no N11/08/256.

REFERENCES

- Fathalla MF, Sinding SW, Rosenfield A, Fathalla MMF. Sexual and reproductive health for all: a call for action. Lancet 2006; 368: 2095-2100.

- Ferraretti AP, Goossens V, de Mouzon J, Bhattacharya S, Castilla JA, Korsak V, Kupka M, Nygren KG, Nyboe Andersen A, European IVF-monitoring (EIM), Consortium for European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2008: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod 2012; 27: 2571-84. Doi: 10.1093/humrep/des225.

- Gordts S. Belgian legislation and the effect of elective single embryo transfer on IVF outcome. Reprod Biomed Online 2005; 10: 436-441.

- Chambers GM, Sullivan EA, Ishihara O, Chapman MG, Adamson GD. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: a review of selected developed countries. Fertil Steril 2009; 91: 2281-94. Doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.029.

- Committee of National Representatives. ART regulation and reimbursement in Europe. Focus on Reproduction May 2015: 22-24.

- Chambers GM, Hoang VP, Sullivan EA, Chapman MG, Ishihara O, Zegers-Hochschild F, Nygren KG, Adamson GD. The impact of consumer affordability on access to assisted reproductive technologies and embryo transfer practices: an international analysis. Fertil Steril 2014; 101: 191-8. Doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.09.005.

- Chambers GM, Adamson GD, Eijkemans MJC. Acceptable cost for the patient and society. Fertil Steril 2013; 100: 319-27. Doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.06.017.

- Huyser C, Boyd L. Assisted reproduction laboratory cost drivers in South Africa: value, virtue and validity. Obstet Gynaecol Forum 2012; 22:15-21.

- Dyer SJ, Kruger TF. Assisted reproductive technology in South Africa: first results generated from the South African Register of Assisted Reproductive Techniques. S Afr Med J 2012; 102: 167-170.

- Ombelet W, Campo R. Affordable IVF for developing countries. Reprod Biomed Online 2007; 17: 257-265.

- Dyer SJ, Abrahams N, Mokoena NE, Lombard CJ, van der Spuy ZM. Psychological distress among women suffering from couple infertility in South Africa: a quantitative assessment. Hum Reprod 2005; 20: 1938-1943. Doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh845.

- Van Balen F, Gerrits T. Quality of infertility care in poor-resource areas and the introduction of new reproductive technologies. Hum Reprod 2001; 16: 215-219.

- Ombelet W, Cooke I, Dyer S, Serour G, Devroey P. Infertility and the provision of infertility medical services in developing countries. Hum Reprod Update 2008; 14: 605-621. Doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn042.

- Hughes EG, Giacomini M. Funding in vitro fertilization treatment for persistent subfertility: the pain and the politics. Fertil Steril 2001; 76: 431-42.

- Fathalla MF. Reproductive health: a global overview. Early Hum Dev 1992; 29: 35-42.

- Murage A, Muteshi MC, Githae F. Assisted reproduction services provision in a developing country: time to act? Fertil Steril 2011; 96: 966-8. Doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.1109.

- Ombelet W, De Sutter P, Van der Elst J, Martens G. Multiple gestation and infertility treatment: registration, reflection and reaction – the Belgian project. Hum Reprod Update 2005; 11: 3-14. Doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh048.

- Kadoch IJ, Al-Khaduri M, Phillips SJ, Lapensée L, Couturier B, Hemmings R, Bissonnette F. Spontaneous ovulation rate before oocyte retrieval in modified natural cycle IVF with and without indomethacin. Reprod Biomed Online 2008; 16: 245-9.

- Ebner T, Moser M, Sommergruber M, Tews G. Selection based on morphological assessment of oocytes and embryos at different stages of preimplantation development. A review. Hum Reprod Update 2003; 9: 251-262. DOI: 10.1093/humupd/dmg021.

- Van Loendersloot L, Repping S, Bossuyt PMM, van der Veen F, van Wely M. Prediction models in in vitro fertilization; where are we? A mini review. J Adv Res 2014; 5: 295-301. Doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2013.05.002.

- Parikh FR. Affordable in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril 2013; 100: 328-329. Doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.049.

- Aleyamma TK, Kamath MS, Muthukumar K, Mangalaraj AM, George K. Affordable ART: a different perspective. Hum Reprod 2011; 26: 3312-3318. Doi: 10.1093/humrep/der323.

- Department of Health. The South African National Department of Health. Health Charter, 11th Draft. Pretoria. Department of Health; 2006.

- Makuch MY, Petta CA, Osis MJ, Bahamondes L. Low priority level for infertility services within the public health sector: a Brazilian case study. Hum Reprod 2010; 25: 430-435. Doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep405.

- Jones HW, Allen BD. Strategies for designing an efficient insurance fertility benefit: a 21st century approach. Fertil Steril 2009; 91: 2295-7. Doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.006.

- Williams SC, Gibbons WE, Muasher SJ, Oehninger S. Minimal ovarian hyperstimulation for in vitro fertilization using sequential clomiphene citrate and gonadotropin with or without the addition of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist. Fertil Steril 2002; 78(5): 1068-72.

- Lass A. Monitoring of in vitro fertilization – embryo transfer cycles by ultrasound versus ultrasound and hormonal levels: a prospective multicentre, randomized study. Fertil Steril 2003; 80: 80-85. DOI: doi.10.1016/S0015-0282 (03)00558-2.

- Golan A, Herman A, Soffer Y, Bukovsky I, Ron-El R. Ultrasonic control without hormone determination for ovulation induction in in vitro fertilization/embryo transfer with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogue and human menopausal gonadotrophin. Hum Reprod 1994; 9: 1631-1633.

- Palmer OM, Grenache DG, Gronowski AM. The NACB Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines for Point –of-Care Reproductive Testing. Point of Care 2007; 6: 265-272.

- Sunkara SK, Rittenberg V, Raine-Fenning N, Bhattacharya S, Zamora J, Coomarasamy A. Association between the number of eggs and live birth in IVF treatment: an analysis of 400 135 treatment cycles. Hum Reprod 2011; 26:1768-1174. Doi: 10.1093/humrep/der106.

- Hohmann FP, Macklon NS, Fauser BCJM. A randomised comparison of two ovarian stimulation protocols with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist co-treatment for in vitro fertilization commencing recombinant follicle stimulating hormone on cycle day 2 or 5 with the standard long GnRH agonist protocol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88:166-173. Doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020788.

- Engel JB, Ludwig M, Felberbaum R, Albano C, Devroey P, Diedrich K. Use of cetrorelix in combination with clomiphene citrate and gonadotrophins: a suitable approach to 'friendly IVF'? Hum Reprod 2002; 17(8): 2022-2026.

- Tavaniotou A, Albano C, Van Steirteghem A, Devroey P. The impact of LH serum concentration on the clinical outcome of IVF cycles in patients receiving two regimens of clomiphene citrate/gonadotropin/0.25mg cetrorelix. Reprod Biomed Online 2003; 6: 421-6.

- Yanaihara A, Yorimitsu T, Motoyama H, Ohara M, Kawamura T. The decrease of serum luteinizing hormone level by a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist following the mild IVF stimulation protocol for IVF and its clinical outcome. J Assist Reprod Genet 2008; 25: 1158. Doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9205-6.

- Savasi V, Mandia L, Laoreti A, Cetin I. Reproductive assistance in HIV serodiscordant couples. Hum Reprod Update 2013; 19: 136-150. Doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms046.

- Savasi V, Ferrazzi E, Lanzani C, Oneta M, Parrilla B, Persico T. Safety of sperm washing and ART outcome in 741 HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. Hum Reprod 2007; 22: 772-777. Doi: 10.1093/humrep/del422.

- Minkoff H, Santoro N. Ethical considerations in the treatment of infertility in women with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1748-1750. Doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006083422312.

- Semprini AE, Fiore S. HIV and reproduction. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2004; 16: 257-262.